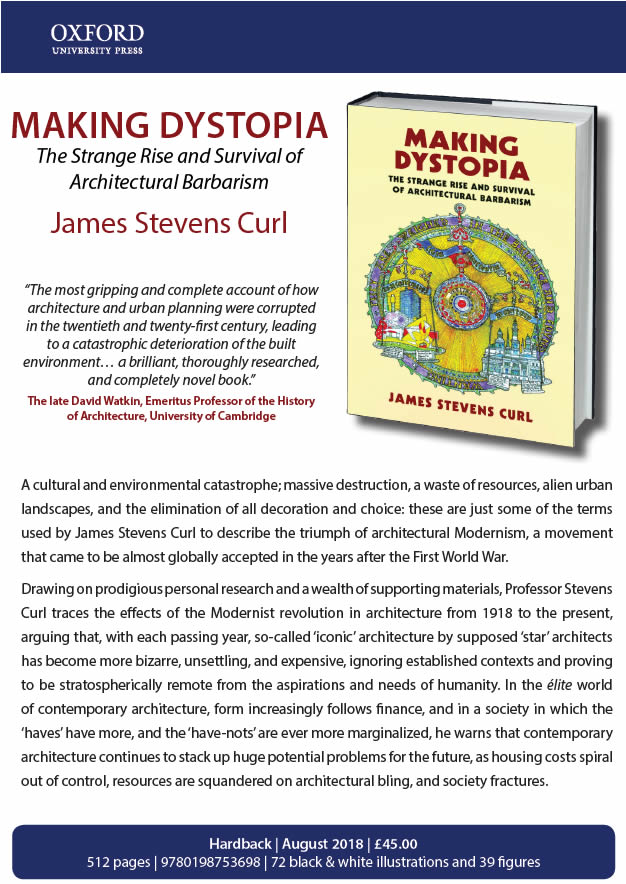

Making Dystopia: The Strange Rise and Survival of Architectural Barbarism

Author : James Stevens Curl

Publisher : Oxford University Press

978-0-19-875369-8 (hbk)

“Making Dystopia, the most gripping and complete account of how architecture and urban planning were corrupted in the 20th and 21st centuries leading to a catastrophic deterioration of the built environment, is a brilliant, thoroughly researched, and completely novel book... This book, surely the greatest of the many written by Professor Stevens Curl, should be read by staff and students in all schools of architecture who are still pursuing destructive, irrelevant, outdated paths, as well as by everyone concerned about the erosion of civilisation itself.” The late David Watkin, Emeritus Professor of the History of Architecture, University of Cambridge

A cultural and environmental catastrophe; massive destruction, a waste of resources, alien urban landscapes, and the elimination of all decoration and choice: these are just some of the terms used by James Stevens Curl to describe the triumph of architectural Modernism, a movement that came to be almost globally accepted in the years after the First World War.

Drawing on prodigious personal research and a wealth of supporting materials, Professor Stevens Curl traces the effects of the Modernist revolution in architecture from 1918 to the present, arguing that, with each passing year, so-called 'iconic' architecture by supposed 'star' architects has become more bizarre, unsettling, and expensive, ignoring established contexts and proving to be stratospherically remote from the aspirations and needs of humanity. In the élite world of contemporary architecture, form increasingly follows finance, and in a society in which the 'haves' have more, and the 'have-nots' are ever more marginalized, he warns that contemporary architecture continues to stack up huge potential problems for the future, as housing costs spiral out of control, resources are squandered on architectural bling, and society fractures.

While this combative critique of the entire Modernist architectural project and its apologists will be regarded by many as highly controversial, Making Dystopia contains salutary warnings that we ignore at our peril and asks awkward questions to which answers are long overdue. Given the unedifying later history of Modernist social housing in Britain, including exemplars such as The Crescents at Hulme, Manchester, Broadwater Farm Estate, Tottenham, north London, the Ledbury Estate, Peckham, south London, and culminating in the incineration of the Grenfell Tower, north Kensington, this courageous, passionate, and profoundly argued book should be read by everyone concerned with what is around us.

Reviews

‘It is one thing to loathe what modernist architects and planners have done to our cities, and another to understand why they did it. This book digs down to the unsavory roots of the Modernist movement. It finds a mixture of pseudo-moralism, cosying to high finance, contempt for the past, for spiritual and aesthetic values, and for the humans compelled to live with its ideals. In short, the whole movement is as rotten as the Grenfell Tower of recent (2017) and tragic memory.

Curl rightly calls it a ‘catastrophe’. Whereas the arts and music of Modernism are a choice, to be ignored at will, avoiding its architecture is impossible. The destruction of the urban fabric touches everyone; the necessity of living in such towers touches those unable to object, except by vandalizing them. The one bright side (except financially) is that many Modernist buildings are being demolished. But the damage done by destroying older buildings and urban areas that could have been renovated is irreversible.

Curl’s own demolition begins, surprisingly, with Ruskin and Pugin, who promoted neo-Gothic as the only morally acceptable style. ‘This moral disapprobation to justify an aesthetic stance has been a dangerous weapon in the hands of International Modernists…’ (p 20). Some Modernists boasted its clean break with the past. Others, like Sir Nicolaus Pevsner, whose Buildings of Britain has endeared him to every amateur of architecture, created a false genealogy for it. This pretended that it started with the German enthusiasm for English domestic architecture and for late 19th-century architects such as Voysey, Baillie Scott, and the Arts & Crafts movement. Curl’s second chapter, ‘Makers of mythologies and false analogies’, shows that the products of this period have almost nothing to do with Modernism as it appeared after World War I.

This summary, which is intended to encourage reading of the book itself, must skid quickly over the chapter on the origins of the Bauhaus. What began by blending Arts & Crafts training with transcendent ideals (in Itten, Klee, Kandinsky) ended with Gropius’ embrace of technology and an ‘aesthetic straitjacket, limiting creation, and in the end failing to make a new world that was worth the effort’. (p 106-7) The next chapter, which introduces Mies van der Rohe, unravels the politics of Modernist architecture in the 1920s and 1930s. Any simplistic attributions of it to Left or Right dissolve among the complexities of shifting political climates in Germany and the Soviet Union. But although those tyrannies have passed, their principles have not: ‘Intolerant dogmatism, lip-service to “scientific” principles without understanding what science is, and pretences to be “objective” have begotten an inhumane world: they threaten to impose a global Dystopia on us all.’ (p 170)

Philip Johnson, Alfred Barr, and New York’s Museum of Modern Art dominate Chapter 5. Curl sees the effect of German émigrés fleeing Nazism as far from benign. Although Modernism’s Teutonic beginnings were now downplayed, a close examination of them ‘induces a deep sense of unease: there can be no doubting the unfeeling authoritarianism, even totalitarianism, at the dark, irreligious heart of Modernism, something that generally has been ignored.’ (p 182) None better fitted this mindset than the Swiss-born ‘Le Corbusier’, perhaps the chief villain of Curl’s history. His simplistic slogans, his ‘propaganda manual for destroying humane architecture and coherent, civilized urban structures’ (p 194), and his ‘monstrous egotism…and infatuation with unsustainable consumerism’ (p 198) lead to another major theme of this book.

That theme is the ‘strange survival’ of the Modernist movement: in brief, that ‘it was intimately linked with commerce, with planned obsolescence, and with vast financial and industrial concerns, without which it could never have been so universally embraced.’ (p 222) After 1945 it posed as the moral alternative to the Nazis’ grandiose ‘stripped Classical’ buildings. Ironically, it was countries like Poland and Germany itself, which had suffered most destruction in the Second World War, that rebuilt their city centres in traditional style.

In the succeeding chapters, Curl illustrates the consequences of the Modernist hegemony, as he had done on a smaller scale with his early book The Erosion of Oxford (1977). Oxford has survived, but more workaday cities like Coventry, Birmingham, Glasgow, and the City of London have not. Curl does not mince words: ‘A colossal crime has been committed against humanity and common sense’, and, quoting Charles Jencks, ‘half of Europe was destroyed due to the alliance of the [Corbusian] dream of Mass Culture and greed.’ (p 302) He is equally unsparing of ‘Deconstructionist’ displays by ‘star architects’ like Gehry and Hadid, which play on the public disaffection with rectilinear Modernism. Some evidently find London’s new towers, the Gherkin, the Shard, the Cheese-grater, and the Walkie-talkie, exciting and cool, if not ‘camp’. This could only happen when high culture, meaning that ‘autonomous reality in which ideas, aesthetic values, and works of art and literature connect with the rest of social existence,’ (p 341, paraphrasing Vargas Llosa) is rated no better than popular or mass culture, which rests on spectacle, image, propaganda, and commercialism. And it is cold comfort to those condemned to life in ‘bog-standard’ flats.

The Modernist rejection of ornament deliberately excludes meaning, symbolism, and the religious dimension, frequently mentioned in the book. But as Curl admits, ‘All monotheistic religions are essentially intolerant’ (p 315). How can one have the spiritual benefits of religion (and the art and architecture that it has always inspired) without the downsides of fanaticism, fundamentalism, and superstition? This question hovers over Curl’s ‘Further reflections’, and it has to be answered before any real remedy can be undertaken.

The book will enrage those with a vested interest in building Dystopia, while predictably living in pleasant suburbs or luxurious apartments. Obviously this reader has agreed with it from the start. What he hopes is that it will penetrate the middle ground, especially architectural students, and help them to see the fraud that has been perpetrated on them and on all of us’

Indefatigable in his ninth decade, Professor Curl has penned a magisterial tour de force that exposes the conceits and folly of architectural Modernism. It exhibits the work of a scholar at the height of his perceptive powers and provides a penetrating and judicious interrogation into one of the greatest shams in the history of architecture. Having already made outstanding contributions in many unexplored tributaries ranging from Freemasonry to Egyptian Revivalism, Curl turns his discerning gaze to what he duly calls a ‘Catastrophe’ in contemporary architecture and design. This indispensable volume highlights the numerous misconceptions about the Modern Movement and illustrates the gross fallacies perpetuated by CIAM and Corbusianity. But make no mistake, this is no mere revisionist account of twentieth-century architecture; it is a surgical takedown of the juggernaut of Modernism and unmasks its baleful manifestations on streets as far as Milwaukee to Brasília while providing dire warnings about the growth and health of our cities and townships. Curl opens our eyes to the cult-like fundamentalism of the Modern Movement and the blind devotion accorded to its chief propagandists, namely Gropius, Mies, and Le Corbusier, who we discover was a self-promoting Fascist ideologue with a puritanical obsession concerning personal hygiene. The myth that the Athens Charter would engender an egalitarian utopia and offer a panacea for the ills of twentieth-century urbanism is closely examined and demolished by Curl, whose unsurpassed combination of wit and erudition shines through on every page. Every subject in this cornucopia of scholarship is scrutinised with superb fluency and élan. Curl’s brilliant text is a timely marvel, and nothing previously published comes anywhere close to this careful dissection of a century of deceit and destruction. The reader will be completely engrossed with the author’s masterful command of primary sources and sage insights about the life and works of neglected figures, including Baillie Scott, C.F.A. Voysey, and Erich Mendelsohn. This is not a work to be read passively but instead must be mined as a vast repository of rich cultural learning about the failures and hubris of modern architectural education, theory, and design. With this invaluable study, Curl solidifies his place as the nonpareil among scholars unafraid to challenge received opinion and the ‘almost Mosaic authority’ of luminaries such as Pevsner, Ruskin, and Philip Johnson. Dystopia is unquestionably a major contribution to the history of architecture and quite possibly the most important publication in Curl’s enormously prodigious oeuvre.

‘The author of Making Dystopia … a spirited, scholarly assault on the tin gods of Modernism …seems about to explode. His rage against the orthodoxies of modern architecture, which has done such a disservice to British cities, is constantly at boiling point … Don’t expect impartiality, therefore, from this analysis of the “Catastrophe” wrought by Modernism … Whatever you may think of its argument, this book’s scholarship is precise. Prepare to be shocked. Not all the gods of Modernism were very nice … Modernists … were authoritarian. Dissent was not tolerated. Experimental ideas became mainstream. The British establishment embraced this Continental trend with a convert’s zeal. German cities such as Nuremberg were restored for their cultural importance; many here, as Coventry was, were flattened … In 1979, a diplomat noted that Britain’s decline was obvious in the seedy appearance of its towns, airports and hospitals. “Unfortunately,” glosses Curl, “things have not improved since then” ’

‘When I was younger, one of my favourite books was James Stevens Curl’s The Victorian Celebration of Death. His latest is much less cheerful … Modernist principles, misunderstood by unimaginative planners, often led to atrocious results. Le Corbusier’s “vertical gardens” became vertical slums, And there is only a sliver of difference between Walter Gropius’s lofty Bauhaus ideals and a crap council estate. Curl’s ambition is to compose the critique of all critiques, joining a tradition of anti-modern alarm which has included E.M. Forster, Orwell, Vonnegut and Prince Charles. And, of course, Evelyn Waugh. In Decline and Fall, Margot Beste-Chetwynde commissioned a new “clean and square” house from Professor Otto Silenus. Dismayed by the result, she soon has it demolished, saying: “Nothing I have ever done has caused me so much disgust” ’

‘In Making Dystopia, distinguished architectural historian James Stevens Curl … issues a call to judgment among architects, art and architectural historians, urban planners and educators to reverse over a century of cultural demise inflicted in large part through architecture’s faiilure to exercise its civilizing role and societal purpose. Juxtaposing dystopia, a condition of dysfunction, with utopia, a region of ideal happiness, he develops the case that the concept of the ideal city as an expression of social order characterized by a symbolic design and formal pattern, has been debased and profaned, mutilated if not annihalated—with moderism’s minimalist, utilitarian tendencies and historical erasure having an alienating, disruptive impact on society at large. Curl thunderously argues that the once respected art of architecture has become “tragically corrupted” owing particularly to economic special interests and surfeit of urban skylines proliferated over the course of the twentieth century that obliterated local identities, historical memory, and social concourse. With particular invective levelled at Corbusianity, CIAM, and American architect Philip Johnson, he derides the crude simplicity of the modernist aesthetic, the abandonment of ornament and sculptural elaboration, the looming dominance and exaggerated scale of towering behemoths, severance of relationality to life and natural surroundings, and the theoretical dogmatism, pervasive global reach and persistence of the Modern Movement in architecture and planning. The role of the past looms large in a narrative in which modernism is viewed as a prodigal that has squandered its inheritance. He condemns the movement for the debasement and denunciation of centuries of esteemed tradition, contributing, not to a centered sense of humanistic belonging within the flow of time, but to dislocation, to an historical vacuum in which swank banter and glib eclecticism replace time honored stadards of construction and emblematized ideals. He decries the loss of accumulated knowledge integral to the future of Western civilization, of qualified marks of experience and expressions of higher learning aimed at human betterment. But the more trenchant purpose of Curl’s analysis is to reaffirm the meaning and role of architecture itself, its import to civic conduct, communal relations and cultural identity. He attributes to architecture the ability to orient social purpose through visual models, animate design and inspired embellishment; he stresses the psychological importance of symbolism and spirituality resonant signage; and he regards the edificatory import of architecture, its capacity to orient the spirit, elevate the mind, ennoble daily enterprise, to encourage social consciousness, enshrine values, memorialize and honor fundamental to human endeavour. …Encyclopedic in scope and meticulously documented, the text reflects a prodigious breadth of knowledge and impeccable scholarship. … Written with passion and eloquence, Making Dystopia is a work of rare intellectual magnitude, to be recognized as an important, imperative contribution to the culture of our times. It promises to be essential reading to [all those] concerned with cultural heritage, with the quality of human life within a built environment, and with architecture’s enduring legacy to the higher aims of civil society’

‘There is no more evanescent quality than modernity, a rather obvious or even banal observation whose import those who take pride in their own modernity nevertheless contrive to ignore. Having reached the pinnacle of human achievement by living in the present rather than in the past, they assume that nothing will change after them; and they also assume that the latest is the best. It is difficult to think of a shallower outlook … In this scholarly, learned, but also enjoyably polemical book, Professor Curl recounts both the history and devastating effects of architectural modernism. In no field of human endeavour has the idea that history imposes a way to create been more destructive … for while we can take avoiding action against bad art or literature, we cannot avoid the scouring of our eyes by bad architecture. It is imposed on us willy-nilly and we are impotent in the face of it. Modern capitalism, it has been said, progresses by creative destruction; modern architecture imposes itself by destructive creation. As Professor Curl makes clear, the holy trinity of architectural modernism—Gropius, Mies, and Corbusier--were human beings so flawed that between them they were an encyclopaedia of human vice. They spoke of morality and behaved like whores; they talked of the masses and were utter egotists; they claimed to be principled and were without scruple, either moral, intellectual, aesthetic, or financial. Their two undoubted talents were those of self-promotion and survival, combined with an overweening thirst for power. Their intellectual dishonesty was startling and would have been laughable had it not been more destructive than the Luftwaffe … Architectural modernism has a pre-history just as it has its baleful successors. Professor Curl traces both with panache and erudition and shows that the almost universally accepted history of modernism is actually assiduous propaganda rather than history, resulting not merely in untruth but the opposite of the truth … The widely accepted narrative of modernism … is that it was some kind of logical or ineluctable development from the Arts and Crafts movement … it is like saying that Mickey Spillane is a logical or ineluctable outgrowth of Montesquieu … Moreover, claiming respectable ancestors is somewhat at variance with equal claims to be starting from zero (as Gropius put it), but such a contradiction is hardly noticed by the grand narrative history of modernism that Professor Curl attacks and destroys. … Curl has written an essential, uncompromising, learned … critique of one of the worst and most significant legacies of the 20th century … His book has a wonderful bibliography, the fruit of a lifetime of reading and refection …. It is a loud and salutary clarion call to resist further architectural fascism’

‘It is one thing to loathe what modernist architects and planners have done to our cities, and another to understand why they did it. This book digs down to the unsavory roots of the Modernist movement. It finds a mixture of pseudo-moralism, cosying to high finance, contempt for the past, for spiritual and aesthetic values, and for the humans compelled to live with its ideals. In short, the whole movement is as rotten as the Grenfell Tower of recent (2017) and tragic memory.

Curl rightly calls it a ‘catastrophe’. Whereas the arts and music of Modernism are a choice, to be ignored at will, avoiding its architecture is impossible. The destruction of the urban fabric touches everyone; the necessity of living in such towers touches those unable to object, except by vandalizing them. The one bright side (except financially) is that many Modernist buildings are being demolished. But the damage done by destroying older buildings and urban areas that could have been renovated is irreversible.

Curl’s own demolition begins, surprisingly, with Ruskin and Pugin, who promoted neo-Gothic as the only morally acceptable style. ‘This moral disapprobation to justify an aesthetic stance has been a dangerous weapon in the hands of International Modernists…’ (p 20). Some Modernists boasted its clean break with the past. Others, like Sir Nicolaus Pevsner, whose Buildings of Britain has endeared him to every amateur of architecture, created a false genealogy for it. This pretended that it started with the German enthusiasm for English domestic architecture and for late 19th-century architects such as Voysey, Baillie Scott, and the Arts & Crafts movement. Curl’s second chapter, ‘Makers of mythologies and false analogies’, shows that the products of this period have almost nothing to do with Modernism as it appeared after World War I.

This summary, which is intended to encourage reading of the book itself, must skid quickly over the chapter on the origins of the Bauhaus. What began by blending Arts & Crafts training with transcendent ideals (in Itten, Klee, Kandinsky) ended with Gropius’ embrace of technology and an ‘aesthetic straitjacket, limiting creation, and in the end failing to make a new world that was worth the effort’. (p 106-7) The next chapter, which introduces Mies van der Rohe, unravels the politics of Modernist architecture in the 1920s and 1930s. Any simplistic attributions of it to Left or Right dissolve among the complexities of shifting political climates in Germany and the Soviet Union. But although those tyrannies have passed, their principles have not: ‘Intolerant dogmatism, lip-service to “scientific” principles without understanding what science is, and pretences to be “objective” have begotten an inhumane world: they threaten to impose a global Dystopia on us all.’ (p 170)

Philip Johnson, Alfred Barr, and New York’s Museum of Modern Art dominate Chapter 5. Curl sees the effect of German émigrés fleeing Nazism as far from benign. Although Modernism’s Teutonic beginnings were now downplayed, a close examination of them ‘induces a deep sense of unease: there can be no doubting the unfeeling authoritarianism, even totalitarianism, at the dark, irreligious heart of Modernism, something that generally has been ignored.’ (p 182) None better fitted this mindset than the Swiss-born ‘Le Corbusier’, perhaps the chief villain of Curl’s history. His simplistic slogans, his ‘propaganda manual for destroying humane architecture and coherent, civilized urban structures’ (p 194), and his ‘monstrous egotism…and infatuation with unsustainable consumerism’ (p 198) lead to another major theme of this book.

That theme is the ‘strange survival’ of the Modernist movement: in brief, that ‘it was intimately linked with commerce, with planned obsolescence, and with vast financial and industrial concerns, without which it could never have been so universally embraced.’ (p 222) After 1945 it posed as the moral alternative to the Nazis’ grandiose ‘stripped Classical’ buildings. Ironically, it was countries like Poland and Germany itself, which had suffered most destruction in the Second World War, that rebuilt their city centres in traditional style.

In the succeeding chapters, Curl illustrates the consequences of the Modernist hegemony, as he had done on a smaller scale with his early book The Erosion of Oxford (1977). Oxford has survived, but more workaday cities like Coventry, Birmingham, Glasgow, and the City of London have not. Curl does not mince words: ‘A colossal crime has been committed against humanity and common sense’, and, quoting Charles Jencks, ‘half of Europe was destroyed due to the alliance of the [Corbusian] dream of Mass Culture and greed.’ (p 302) He is equally unsparing of ‘Deconstructionist’ displays by ‘star architects’ like Gehry and Hadid, which play on the public disaffection with rectilinear Modernism. Some evidently find London’s new towers, the Gherkin, the Shard, the Cheese-grater, and the Walkie-talkie, exciting and cool, if not ‘camp’. This could only happen when high culture, meaning that ‘autonomous reality in which ideas, aesthetic values, and works of art and literature connect with the rest of social existence,’ (p 341, paraphrasing Vargas Llosa) is rated no better than popular or mass culture, which rests on spectacle, image, propaganda, and commercialism. And it is cold comfort to those condemned to life in ‘bog-standard’ flats.

The Modernist rejection of ornament deliberately excludes meaning, symbolism, and the religious dimension, frequently mentioned in the book. But as Curl admits, ‘All monotheistic religions are essentially intolerant’ (p 315). How can one have the spiritual benefits of religion (and the art and architecture that it has always inspired) without the downsides of fanaticism, fundamentalism, and superstition? This question hovers over Curl’s ‘Further reflections’, and it has to be answered before any real remedy can be undertaken.

The book will enrage those with a vested interest in building Dystopia, while predictably living in pleasant suburbs or luxurious apartments. Obviously this reader has agreed with it from the start. What he hopes is that it will penetrate the middle ground, especially architectural students, and help them to see the fraud that has been perpetrated on them and on all of us’

‘Modernism died—or so Charles Jencks claimed—with the 1972 demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe slab blocks, and yet it continues its grip … today, an abandonment of the past unprecedented in architectural history, and despite sweeping social and political change. What is the secret of its allure? James Stevens Curl has an answer: his new book, Making Dystopia, pulls no punches in describing the … logical incongruities that were embedded into the origins of the “cult” of modernism. It outlines the numerous and ironic failures of many of the figurehead buildings of the functionalist style, the damage caused to urban planning and development, and modernism’s eventual metamorphosis into deconstructivism, parametricism and the “ ‘iconic’ but flaccid erections” of many stararchitects. Making Dystopia is meticulously researched and convincingly argued: it is an undoubtedly controversial book that empties out the contents of modernism for all to see and holds them up to the light for judgement. Curl describes its conceptual origins with CIAM and the Athens Charter, its improbably successful rise through sloganeering; and the unscrupulous tactics of some of its high priests. [He] criticises the modern movement for its conscious anti-historicism, something he likens to the burning of books or destruction of idols. In his view, it is only with careful study and appreciation of the past that we can design buildings that are not only sensitively conceived but also actually appreciated by the public, which “not only has a right to judge [architecture’s] quality, but has the only right so to do”. He urges contemporary design to see itself as a continuation of the past, not a denial of it. Professor Curl’s credentials are undoubted: he compiled The Oxford Dictionary of Architecture, … and is the author of over 40 books as well as numerous articles. This book draws on all this knowledge, and its weighty judgement is not to be taken lightly. Here, finally, is an authoritative critique of the all-pervasive nature of modernism. [It] is a must read for students of architecture: a contentious, highly thought-provoking study, … a call for an appreciation of contextuality and historicism, urging architectural education out of the “compound”. Despite this weighty theme, it is also in places very funny … Not everything in this book will be agreed with, and no doubt many feathers will be ruffled, but, armed with an appreciation of the views it outlines, we might avoid what Curl describes as the “flabbiness, shallowness, and superfluities of so much ‘modern’ architecture” ’

‘Curl shows, in this powerfully argued polemic, … what happened when a handful of egotistical charlatans imposed modernist architecture on the rest of us … [He] tells the story with passion and conviction, and fully justifies his judgment of the modern movement and its aftermath as a catastrophe … [There are] a hundred other questions … left hanging in the air at the end of the book. But thank heavens for an author who is prepared to raise them’

‘A storm is brewing in the world of architecture thanks to James Stevens Curl’s lightning bolt of a book, Making Dystopia … although Curl’s polemic is fierce, and well-written to boot, it is far from a blinkered rant. As one would expect from the author of previous revelatory books on the art and architecture of freemasonry, the Egyptian Revival, and the Victorian celebration of death, Curl’s research has been forensic. … Where Curl’s heroes … produced beautiful, crafted work that was both original and steeped in the classical tradition and did not talk a lot of nonsense about “morality”, “objectivity”, or other drivel obsessed about by Modernists, the architecture created by Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier and their acolytes today has resulted in a “nightmare world of waste, inhumanity and uninhabitable buildings and cities”. And this will only get worse as banal global architecture, together with a woeful lack of town planning, spreads. Essentially what he is saying … is that smooth talkers and various freaks, thugs and oddities with no design abilities managed to destroy a continuous tradition of history and craftsmanship’

‘James Stevens Curl, a veteran architectural historian with a string of big books to his name, certainly tells us what he thinks, and doesn’t spare the presses either. This massive cri-de-coeur must run to more than 250,000 words, including nearly 200 pages of footnotes, glossary, bibliography, and index. Argued with a patholological attention to detail, … it is intended primarily to shock and awe the architectural establishment itself … Curl’s blistering broadside would be a fabulous read for the non-specialist … entertainingly apoplectic … his book reads like an outpouring of pent-up anger, contempt, revulsion, and despair accumulated over decades. He traces what he calls “the Catastrophe” of 20th- and 21st-century architecture back to its roots in the Bauhaus group of architects, gathered together by the devious Walter Gropius in Germany just after the First World War. They were a dodgy bunch, exhibiting a cult-like adherence to dubious ideas—and not just about architecture … Curl’s thesis is that modernist architecture is not far removed from Nazi ideology. Both … shared the same thread of “ruthlessness and sense of superiority”, as well as a “curious remoteness from any sense of reality; a rejection of the world as it existed and a desire to destroy it; and a fanatical adherence to some ‘radiant’ future world that only had its reality in minds from which all compassion had been eradicated”. At the “dark irreligious heart of modernism”, he concludes, was “unfeeling authoritarianism, even totalitarianism”

Making Dystopia, the most gripping and complete account of how architecture and urban planning were corrupted in the 20th and 21st century leading to a catastrophic deterioration of the built environment, is a brilliant, thoroughly researched, and completely novel book. It is full of information about architects and buildings which will be unfamiliar to many readers, and at the same time has a topical theme in that it is fired throughout by a convincing onslaught on the devastation of countless towns and cities by architects whose buildings are analysed in chapters with titles such as 'Dangerous Signals' and 'Descent to Deformity'. It records that a great British architect, Sir Edwin Lutyens, foresaw this decline when he wrote that 'the experience of 3000 years of man's creative work cannot be disregarded unless we are prepared for disaster,' and points to the damage caused by 'the obliteration of history’ that is ‘high on the agenda of Modernist architects'. Much of the blame for this can be placed on the absurdly narrow, wrong-headed, biased, but unaccountably influential rhetoric of Nikolaus Pevsner. This book, surely the greatest of the many written by Professor Stevens Curl, should be read by staff and students in all schools of architecture who are still pursuing destructive, irrelevant, outdated paths, as well as by everyone concerned about the erosion of civilisation itself.

LinkedIn

LinkedIn  Wikipedia

Wikipedia